NY Review: The impossible choice facing a French Jewish family in "Prayer for the French Republic"

…plus a quick spring preview—the most exciting time in the New York season is upon us!

Hello play-goers! I’m back with a review of an excellent play shown on Broadway this season, “Prayer for the French Republic.”

Spring Preview

But first, we’re entering the most exciting time in the New York theatre season: a spate of openings in March and April in the run-up to the Tonys. (More on that here in the New York Times’s full spring preview.) Here are my top picks for shows opening soon.

An exciting revival of Kander and Ebb’s classic, “Cabaret,” is coming to New York from London, featuring Eddie Redmayne and Gayle Rankin. (I’ve got a ticket for the fourth preview!)

Another revival to watch for is The Who’s “Tommy,” a rock opera which tells the story of the abuse and ultimate triumph of a disabled boy in the mid-20th century. Fresh off a well-received run at the Goodman in Chicago, I’m excited for this because my high school did a great production of it, and I’ve never gotten to see a professional production. The score is fabulous—this is a great choice for those who like rock music!

In terms of new works, it’s a bonanza for musicals. One of my favorite contemporary composers, Shaina Taub, is making her Broadway debut as full composer/lyricist with “Suffs,” the story of the Suffragettes fighting for the vote. It got mixed reviews in its premiere off Broadway last season; I’m betting it’s been improved. Her scores are infectious regardless (check out a sample song on the show’s website).

Rachel Chavkin (“Hadestown”) directs “Lempicka,” a new musical about Tamara de Lempicka, a globe-trotting, bisexual, boundary-pushing Polish modern artist. The score from Carson Krietzer and Matt Gould leans pop; check out a sample song on the show’s website. Above all, I trust Chavkin to make this great!

The Alicia Keys musical “Hell’s Kitchen” is making a quick transfer from its off-Broadway premier in the Fall; see my review here.

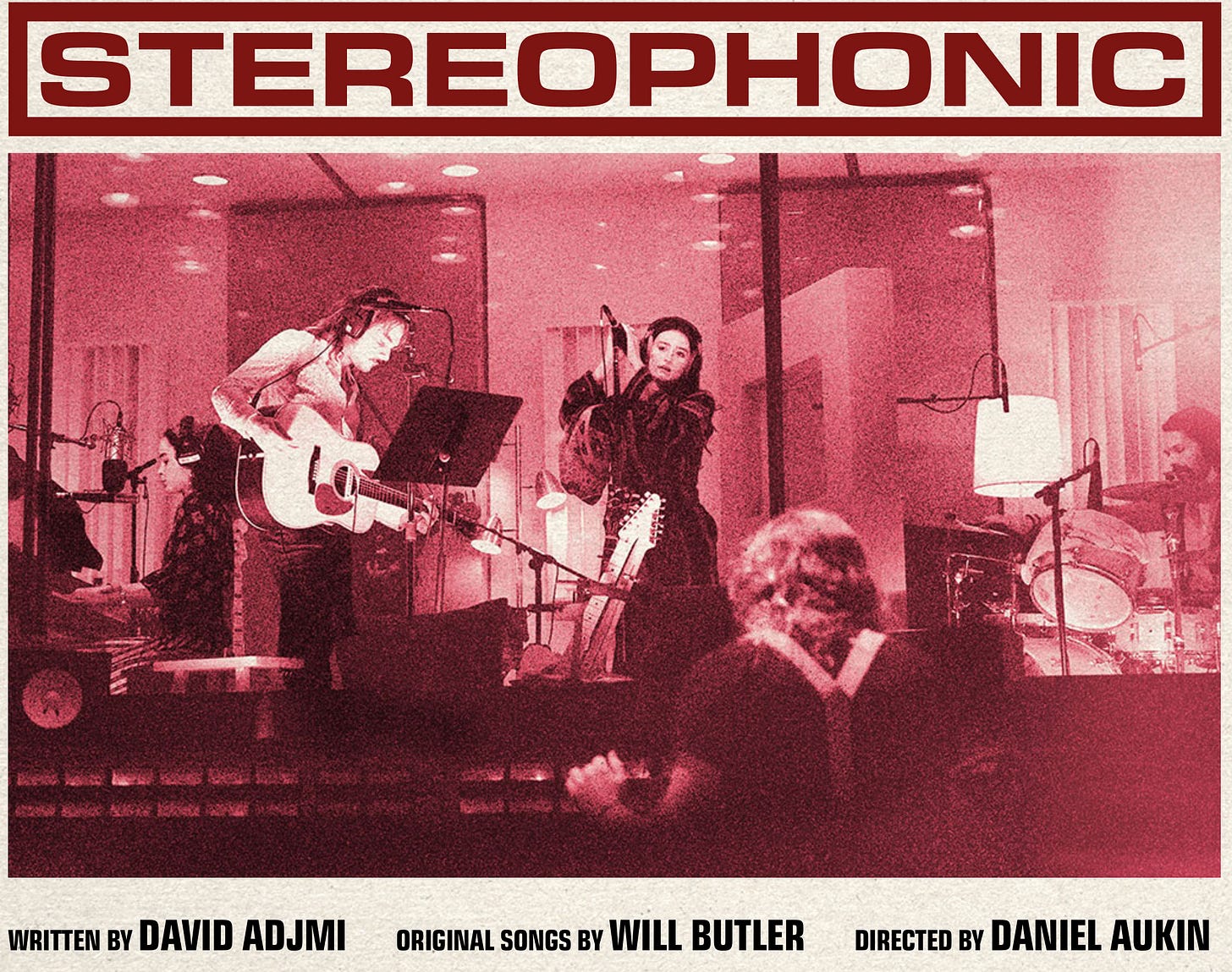

“Stereophonic,” a play with music by David Adjmi about a band in the 1970s recording an album and all the drama that comes with that, has been called the best of the year by many critics, one of whom said she barely breathed during the play’s 3 hour run time. I’ve got a ticket for the third preview!

For those who prefer a straight play, there are several good options. My top two are as follows. A revival of “Doubt” just opened to near-unanimous raves. Familiar to many from the film version, the play centers on a nun (Amy Ryan) who accuses a priest (Liev Schreiber) of sexually molesting a boy. See this if you want a gripping drama.

Finally, “Appropriate” is a family comedy/drama from Branden Jacobs-Jenkins about an Arkansas family reuniting to sort through their recently deceased father’s belongings. In addition to confronting their own (many!) individual and family issues, they find Klan memorabilia, forcing a reckoning with who their father might have really been. Sarah Paulson leads a terrific ensemble in an excellent production. I saw it and highly recommend it!

Personalized Recommendations

As a reminder, I offer personalized recommendations for shows to all my subscribers. Just email me the dates you’re coming to NYC or DC, what your general tastes are, any shows you’re considering, and I’ll send you a few options!

Review: “Prayer for the French Republic”

Stay or go? That’s the question at the heart of Joshua Harmon’s absorbing new play “Prayer for the French Republic,” which closed its run Sunday, March 3 at Manhattan Theatre Club’s Samuel J. Friedman Theatre.

Facing that impossible choice is a French Jewish family in 2016, when increasing antisemitic attacks and the rise of Marine Le Pen’s National Front party make them fear for their safety. That choice is also core to the experience of their great-grandparents’ family, shown in alternating scenes from 1944-46.

Our way into this story is via Molly (Molly Ranson), a Jewish American college student studying abroad in France. She’s come to visit her distant cousins in Paris. No sooner has Molly been welcomed by the matriarch of the family, Marcelle (an excellent Betsy Aidem) when her husband Charles (Nael Nacer) and son Daniel (Aria Shahghasmi) rush in: Daniel has been physically attacked, likely motivated by anti-Semitism. He is teaching at a Jewish school and has begun wearing a kippah.

Marcelle insists that Daniel wear a baseball hat over his kippah to protect him for future attacks. “Why can’t he be private” about his identity, she insists. But over the ensuing scenes, her husband begins to feel unsafe, too, and determines he wants to move the family to Israel. Marcelle disagrees, and that decision dominates the rest of the play. Over three hours that feel like much less, the characters debate the difficult choice.

Interwoven are scenes of the family’s forebears during World War II. At the outset of the war, that generation splits up—some family members go to Cuba, while Marcelle’s great-grandparents are miraculously able to ride out the war in their Paris apartment. However, Marcelle’s father and grandfather are arrested by the Nazis and sent to concentration camps. Marcelle’s father and grandfather survive the concentration camps and come back to the apartment, where they try to pick up where they left off with their family piano business. The play sets up a powerful dialogue between the two time periods.

I was drawn to this play in particular because I’ve been grappling with my own Jewish identity a lot in the last few months. I wear a Star of David necklace and can choose whether to put it on top of my shirt or hidden underneath. That constant choice is more fraught right now, when being Jewish feels more precarious given the Hamas attack and an uptick in anti-Semitism. So I found it fascinating seeing the variety of Jewish identities presented in the play, and how those affect the characters’ views on what to do as conditions turn against Jews. Marcelle’s father married a Catholic woman after surviving the concentration camps, an interesting turning away from his Jewishness. Perhaps as a result, Marcelle and her brother, Patrick, grew up mostly secular. Patrick has almost completely assimilated and doesn’t understand why Marcelle can’t just do the same and stay put. Meanwhile, Marcelle’s husband is a Jewish Algerian immigrant who fled his home country during a crisis for Jews there. The couple raise their children “traditional but not religious,” as Marcelle puts it. This youngest generation has their own varieties of Jewish identity: for Daniel, its central to his self-concept while for his cousin Molly, its her heritage only: as she puts it, she’s merely “of Jewish extraction.”

Each character is well-crafted and expertly realized by the strong ensemble. They bring naturalism and vulnerability to their roles, hitting both the comedic notes and the currents of fear running beneath everything. Director David Cromer adds little in the way of wiz-bang, keeping the attention on the very good writing. He places his characters on a giant turntable that takes up almost the entire stage. Slowly turning back and forth, it allows for smooth transitions, and makes the 1940s scenes feel connected to the present-day ones. Takeshi Kata’s scenic design also includes a few minimal set pieces to show two Paris households, otherwise leaving vast open space to hold the big ideas being discussed. Lighting design by Amith Chandrashaker helps to focus our attention but still leaves the rest of the space visible. The overall effect makes the people feel small and the ideas feel big.

With any invisible or semi-visible identity, one faces a daily choice in how to share, or conceal, that self with the world. Gays may butch it up, Jews may eschew the kippah, people with hidden disabilities may choose whether to disclose. And so on. The play asks us: Can hiding your Jewishness spare you from attack? During an argument with Marcelle, her brother Patrick says, “In a hundred years our family will still be here; where will you be?” While he’s talking literally about her potential move to Israel, I think he also means his family will survive because they have assimilated and don’t show their Judaism publicly. The line infuriated me for the false sense of agency over a Jewish person’s safety it assumes. Over and over again in history, no matter whether or not they were assimilated in their adopted countries, there came a time when Jews were killed or driven out.

The play was written before the start of the war in Gaza this past Fall and takes place in 2016. Even so, we are seeing it now after the October 7 attacks by Hamas that have made the promise of Israel as a place of safety for these Jewish characters more suspect. The war has raised new and old critiques of Israel to the forefront; I have been very disappointed witnessing what Israel is doing to Gaza and its people. The characters confront some of these issues, especially Molly, who makes the harshest critique of Israel. A brilliant scene with her and Elodie brings out the differences in the American Jewish and French Jewish experiences. As Elodie points out, it’s easier for American Jews to criticize Israel when they have no imminent feeling of danger, whereas French Jews carry a near-living memory of Nazi occupation. For them, whatever criticisms they may hold of Netanyahu’s government, the occupation in the West Bank, and the brutal conditions for Gazans—and Elodie has many sharp critiques of these—take a backseat to their fundamental reliance on Israel as a refuge. (For a play more focused on the problems of Israel-Palestine, check out the Public Theatre’s “The Ally.”)

It’s a high compliment to a three-hour show that you want even more as it comes to an end: more time with the past generation; more backstory on Marcelle’s husband’s Algerian background; more on Elodie’s mental health challenges. As the play reaches an uncertain conclusion, the characters all try to answer this question: “Why do they hate us?” They each attempt an answer, but none feels completely satisfactory. Maybe there is no single reason beyond Jews’ difference—the same reason so many groups are hated and attacked.

As I reflected on the play more in the days following, I realized it raised one more question which transcends the Jewish experience: when a society is taking a dangerous turn toward tyranny, what should citizens—especially traditionally persecuted minorities—do: stay or go? This dilemma was present in the 1930s-40s with the rise of Fascism and the play illustrates comparable dangers in 2016 France. Perhaps we can relate here in the United Stated in a pivotal election year that has many fearing for the future. The spread of tyranny and intolerance is a never-ending concern throughout the world. I hope for a future when persecuted groups will not have to confront the same dilemma facing the characters in this play.

***

That’s all for now! As always, send me your thoughts on these and anything else you’ve seen!